John Bagg (1828-1900) and Hannah White (1834-1900) were both born in rural Dorset from working class families. Hannah, the daughter of Joseph and Sarah White was born in the village of Piddletrenthide. John the son of Joseph Roberts Bagg (1801-1882) and Ann Vincent (1799-1874,) was christened in the village of Cattistock. John and Hannah were married on June 24th, 1852 at St. Nicholas Anglican Church, Sydling. Their marriage was to be the start of a dynasty spreading across the world, with living descendants today in Canada, Australia, Wales and England.

John and Hannah had 12 children: Eliza Ann White Bagg (June 14th, 1852 – 1925) Eliza married John Denning of Weymouth, Dorset, where the couple operated a green grocer shop. They had 8 children.

Emma Jane Bagg was born October 13th 1853; Joseph John White Baggs (March 6th 1856 Piddletrenthide – July 19th, 1930) Joseph emigrated to Newcastle, NSW, Australia where he worked as a coal miner and married Mary Jane Gills (1865-1940) they had 6 children.

George Bagg (July 15th, 1857 Piddletrenthide – May 12th 1951) George married Mary Jane Shaw (1858-1937) and farmed near Woolbridge, Ontario with their 4 children. And James Bagg born June 2nd, 1859 at Piddletrenthide married Catherine Morris and lived near Toronto Junction with their 5 children.

Elizabeth (Bess) Bagg was born July 15th 1861 at Weston, Portland. She married William Bull (1866-1920) at Beaufort in Wales, where they raised a family of 6 children. Bess died on December 30th 1950.

John and Hannah then moved to Weymouth where Frederick William Bagg was born on July 28th 1865. Fred had 4 children with his first wife Annie Dennis (1870-1897) and 3 more children with his second wife Jennie Bishop (1867-1949). Fred was a successful farmer near Guelph, Ontario. He died on September 28th, 1940.

In 1867 on November 28th, Harry (Henry) Bagg was born. Harry married Alice Dennis (1862-1942) and they had 7 children. They operated a successful farm in Downsview now in the City of Toronto.

Thomas Bagg was born in 1869 and married Margaret Graham (1873-1920.) The couple had 3 children. Thomas, who died on August 6th 1942, was a farmer and thresher at Downsview.

William George Bagg was born at Llagattock, Crickowell, Wales in April 1871 and died at just 7 months.

Walter Bagg born May 16th 1874 at Crickowell, Breconshire, Wales died in 1942. He married Charlotte Duncan (1872-1954) and had 7 children. They homesteaded on the unsettled Saskatchewan prairie near Springside, in 1900.

John and Hannah’s youngest child, William Charles Bagg, was born on July 29th 1877 at Crickowell. Bill married Blanche Hadden and they had 7 children. Bill and Blanche also homesteaded near Springside, Saskatchewan, and operated some grain elevators. They eventually retired in the Rocky Mountains near Trail, British Columbia. William died on October 21st, 1953.

The Bagg family moved frequently in search of work. They originally lived near the rural villages of Sydling and Piddletrenthide. Here, like many of his family, John worked in the fields as a general farm labourer. This was a time in British history when mechanisation was replacing the need for farm labourers. The agricultural based economy of rural Dorset County provided fewer and fewer employment opportunities. Industrialisation was underway and many people were forced to move from farm cottages to city slums in search of employment. The working class struggled to survive.

In search of employment, John moved his family to Portland, Dorset, where manual labourers were required to work in the limestone quarries. Long hours, low wages, harsh working conditions and child labour were the norm. The Census taken on April 7th, 1861 has John listed as a labourer living at the top of the steep slope above Fortuneswell on Yeats Road with his younger brother George Bagg (1835-1916) and his family. George is described as a “carter,” which means he worked with teams of horses or mules and a cart used to move materials in the limestone quarry. Hannah (6 months pregnant) and their young children Emma (7), Joseph (5) and James (1) were living about 20 miles away, on the Doles Ash Estate, near Cerne Abbas. Hannah is listed as a “farm servant.” Eight year-old Eliza was sleeping over at her White grandparents’ home at Lower Sydling.

A short time later, Hannah and the children joined John in Portland. Hannah gave birth to daughter Elizabeth (Bessie) at the small Portland village of Weston on July 15th 1861. They later lived for a few years at nearby Weymouth, where John likely worked at the harbour.

Their first-born son Joseph left home with a friend at 14 years of age, about 1870, and emigrated to Australia. He married and settled in Lambton, Newcastle, New South Wales and worked as a coal miner. Joseph worked in the mines for the rest of his life and many of his descendants are still living in Newcastle today.

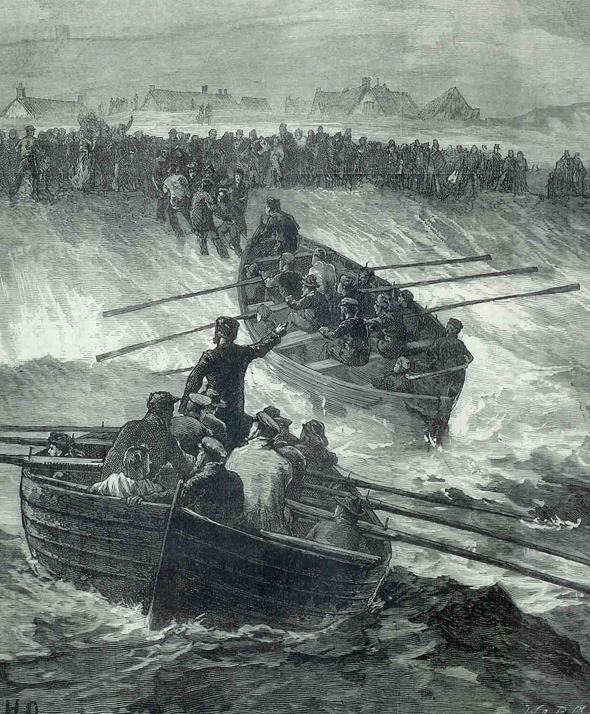

Times were still very difficult for John and Hannah and their family, so about 1870 they moved to Wales to look for work in the coal mines and steel foundries. They worked in the coal mine at Llangattock, Breconshire for what was likely subsistence wages in chronically dangerous conditions. It was still very difficult to get ahead financially. Even the young children were expected to work. When she was 12 years of age, Elizabeth (Bessie) went to work as a domestic for the Ebbw Vales Ironworks Company Shop.

John’s younger brother George Bagg (1835-1916) had previously left Portland limestone quarries and moved his wife Mary Ann Porter (1832-1907) and two children, James (1854-1932) and Martha (1856-1941) to Ontario, Canada. They had emigrated in 1871 and were already doing quite well farming near Toronto. George encouraged John and the family to leave Wales and come to Canada. Their decision to do so was a turning point in their lives.

In 1880, John, Hannah and seven of the sons (George, James, Fred, Henry, Thomas, Walter and William) emigrated to the Weston area, near Toronto. George and his “little brother” Walter came to Canada first with their friends, the Mellings family. The family bible states “March 28 1880, leaving for America.” The rest of the family followed several months later. John and Hannah farmed in Downsview on Jane Street and Wilson Avenue. John also kept the tollgate at Wilson Avenue and Weston Road. These areas are now part of the City of Toronto. With the help of their seven sons, John and Hannah lived a happy and prosperous life. They were able to watch their many grandchildren grow up and establish their own farms, businesses and professions.

In April 1900, just as William and Walter were preparing their move to homesteads on the Saskatchewan prairie, John and Hannah died within a week of one another. They are buried together in the Weston Riverside Cemetery. The large “Bagg” tombstone is shared with George and Mary Ann Bagg. Also memorialized on the tombstone are John and Hannah’s grandson Arthur Bagg (1892-April 9, 1918,) who was killed in France during World War 1, and their great-grandson, Sgt Murray John Henry Bagg (1918-July 12, 1944,) who was killed at Caserta, Italy during World War II.

On July 1st 1930, 50 years after John and Hannah’s arrival in Canada, the first Bagg Family Reunion was held at the farm of Harry Bagg in Downsview. This was attended by 130 of the Ontario descendants of John and his brother, George. It is amazing to see how prolific and successful the family of John and Hanah Bagg has been in the last 150 years. There are now over 700 known descendants in Ontario, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Australia, England and Wales. Like their 19th century ancestors, these Bagg descendants possess a strong work ethic, and a close sense of “family” that includes providing improved opportunities for the following generations.