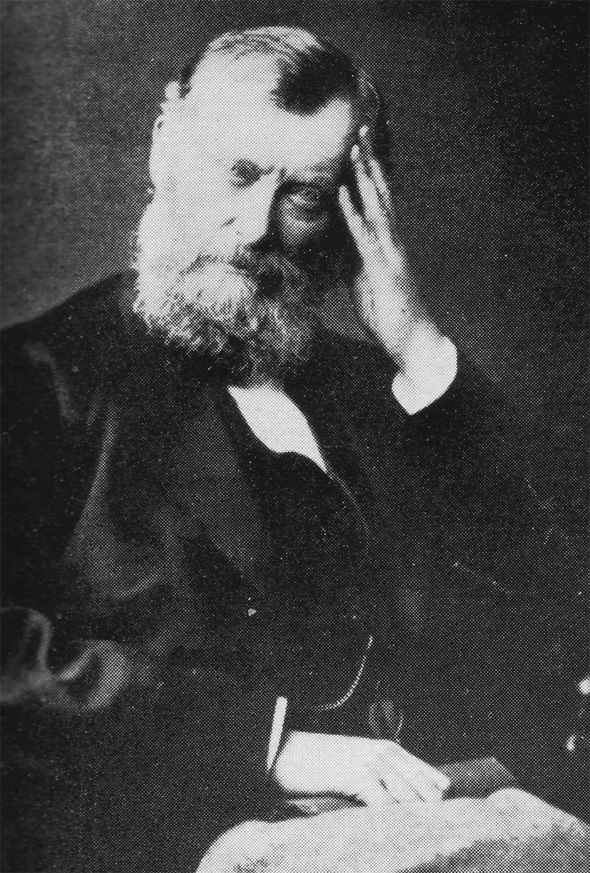

Cardinal John Morton was not the only clerical figure with Dorset connections to have become Archbishop of Canterbury; the position of Protestant Primate of England was also attained by another man of the county. But William Wake, born 348 years ago this January (2005) probably had the more distinguished pedigree of the two men.

Wake was born on January 26th 1657 in the village of Shapwick near Badbury Rings, the only child of a family of five children to survive to adulthood. His father was Colonel William Wake senior, a distant descendant of the Saxon warlord Hereward the Wake, who led an insurrection against William 1 in 1070 (not, as is widely believed, that he came over with the Norman conqueror).

William senior (the Colonel) had joined a Cavalier regiment when still young and had suffered much for the Royalist cause during the Civil War. This included being imprisoned more than twenty times and even being condemned at Exeter to be hung, drawn and quartered for complicity in the western insurrection, but was later pardoned. Colonel Wake married Amy Cutler, daughter of Edward Cutler, a prosperous Stourpaine farmer. Said to have been strong and hard-working, Amy brought he husband considerable wealth, but was nevertheless to die of tuberculosis when young William was only 16.

When he was six William attended his first school in Blandford. At 16, by then a gifted scholar, his father sent him to Oxford where he matriculated as a Commoner in 1673. Two years later he became a student, going on to gain a BA in 1676 and then an MA in 1679. Colonel Wake, keen to see his son follow a clerical career, advised him to take holy orders when he reached Canonical age, and consequently in September1681 William was made a Deacon. The following year he was ordained as a Priest, then becoming Chaplain to Louis X1V court in 1682. Wake remained at the French court until 1685.

In 1688 Wake married Ethelreda, daughter of Sir William Howell of Norfolk, and by her raised a family of 13 children. Their father became Canon of Christchurch, Oxford, also being presented to the Rectory of St James, Westminster. As a reward for his support of the Accession of William and Mary, the King and Queen appointed Wake Canon of Exeter Cathedral in 1701. Following a brief period at the Bishopric of Lincoln (where he was made Clerk of the Closet) William was installed as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1715.

But by this time the Archbishop had been pursuing a parallel career as a Parliamentarian for 10 years. Wake had taken his seat in the House of Lords in 1705, but found its demanding workload too much for his somewhat frail constitution to endure. The additional demands upon him left William with almost no time to indulge his other intellectual interests of researching, translating and collecting.

In his latter years he was able to take up work again, but a decline in his mental faculties and other health problems hampered his efforts. His many friends rallied to help him produce several valuable manuscripts which he bequeathed to Christchurch College, together with his expansive collection of books, coins and medals. As a writer he gained a reputation for outspoken-ness and many of his theological works became controversial. At one time a concern over what he regarded as bad language and moral laxity caused him to attempt to force a blasphemy bill through Parliament to punish offenders.

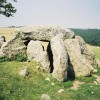

Like so many other Dorset men Wake had the greatest affection for his native county. On one occasion members of the Society of Dorset Men even invited him to preach at Mary Le Bow Church, a proposition which brought him much delight and satisfaction. Whenever he was staying at the family home in Shapwick Wake would preach at St Andrews in Winterborne Tomson. This 12th century church was the Archbishop’s favourite and would be visited repeatedly whenever Wake was on his native patch of soil. He generously covered the cost for providing St Andrews with ten more box pews. He said he found the calm atmosphere refreshing after the great cathedrals.

The Archbishop was also a great champion of free education, considering that every child, regardless of status, should have an equal opportunity to learn. In his day this generated opposition, but in his will, Wake made provision for £1,000 to be paid to the Corporation of Blandford for the schooling of 12 pauper boys. This paid for a schoolmaster, who would supply books,writing materials and accommodation for the boys. The trustees were required to supply the boys with a blue gown, breeches, yellow stockings, shoes, cap, belt and bib at Whitsun.

Thus Blandford’s Blue Coat School was born. The boy’s education was conducted under strict rules to prepare them for work in the trades and industries of the town – and to follow Protestantism. Under the Education Act of 1944 and 1946 the charity was wound up, and in 1974 a new Primary school in Blandford was dedicated as “The Archbishop Wake Junior School” by the Bishop of Sherborne.

Finally, one might think that an Archbishop of Canterbury born in Dorset, would have been buried either in that Cathedral or Dorset, but this was not the posthumous fate of Archbishop William Wake. When he died, on his 80th birthday in 1736, he was laid to rest in the parish church in Croydon.