Around 1800 BC invaders from the Rhineland settled Britain, bringing with them a pagan tradition that emphasised the importance of stone sanctuaries rather than mere earthworks as foci of old religion ceremonial or ritual. The Beaker Folk as these people were called (after the style of their pottery) left behind many standing stones arranged in rows, avenues, circles, and in isolation, in the highland and lowland regions of the UK. Stonehenge is only the most sophisticated and large-scale of these ceremonial centres, but many far more minor stone circles were constructed.

The Beaker and later Bronze Age people of Dorset left a legacy of about six stone circles, mainly in the south of the county. Some have virtually disappeared while others have been damaged, either through natural erosion or subsidence, or by man’s actions.

About halfway along the B3351 between Corfe and Studland and in the north shadow of the Purbeck Ridge below Nine Barrow Down lies Rempstone. This is the site of a hitherto unknown and ignored stone circle, as it is not shown either on the first OS map of the 1890’s, or even the present Internet Megalith Map. Yet the circle must once have been a complex and impressive one, and Cope mentions it in ‘The Modern Antiquarian’ as being lost in undergrowth, neglected, obscured, and cut by ditches and embankments. The site remained in this condition until 1966 when the enclosing woodland was felled to open it up to the view from the road, and new saplings planted nearby.

Ten stones have been relocated at Rempstone: a few standing, some nearly complete, with others lop-sided or sunk through subsidence. Surveying has found that some of the stones would have stood almost 6 feet high while others would have been less than knee height. Another recorder has noted four stones 4 feet high, and another four large stones fallen. These form a half circle 80 feet across, later sliced in two by a bank and ditch.

To the south the area has largely been cleared, with rocks piled together a short distance to the east. This pile comprises eight identical stones, and it has been suggested this feature could represent the remains of a large outlier subsequently collapsed. The stone nearest to the road is speckled with holes and cracks, which were found to have a number of coins wedged into them. Other stones related to the circle are scattered throughout the present wood.

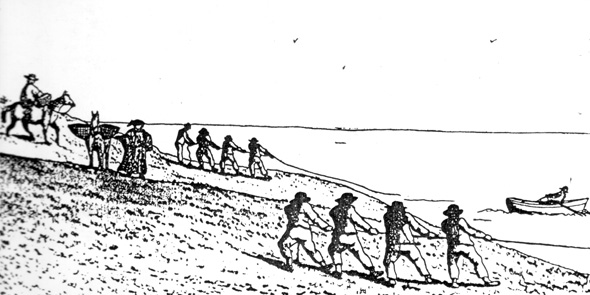

In 1957 a local farmer ploughing his field half a mile to the west of the main site uncovered 26 stones arranged in two rows to form an avenue three yards wide. This avenue was found to be aligned directly with the circle, and is thought to indicate that the Rempstone Circle has – or had – alignments to mark the autumn and summer equinoxes. Another 23 stones about 2 feet 6 inches long were found in the field immediately south of the B3351, and west of the track from Rempstone Farm. Were these once part of a ceremonial way or a line of sighting to the circle?

Besides being impressive, the Rempstone Circle is also unusual. It was sited along the foot, rather than the summit of a ridge or downland favoured in most other cases, including other sites in Dorset. But it has been pointed out that it would have been in easier reach of the Bronze Age populations both on Nine Barrow Down and living in the Purbeck heath area. Another mystery is that one researcher found unexplained light effects on a photograph of one of the stones which resembled fairies or elemental spirits.

Other Circles. There is a stone circle at a focus of paths on a downland knoll about 1 km south east of Lower Kingston Russell (OS SY577877; Landranger Sheet 194.) This has been described as an unimpressive ring of slabs (assumed to be fallen, as recumbent stone circles are not otherwise known in southern England.) The circle is a scheduled ancient monument, but is not mentioned by Burl in his impressive treatise ‘Stone Circles of Brittany, Ireland and Britain.’ This monument is more impressive from the air, but any further information about it is clearly needed.

Just over 4 km to the NE of the Kingston Circle however, stands the much better known and protected Nine Stones near Winterborne Abbas (SY 661904;LR194.) Owing to its good preservation and situation directly on the south side of the A35, this monument, in the eastern corner of a block of woodland, has been fenced off and gated, though with access to the enclosure.

This circle has very large and very small stones ranging from 90 cm to 3.4 metres, which Burl has suggested may represent sex symbols. Some have also noted some influence of the Caledonian or northern highland circles in the Nine Stones, and small clay objects like elongated dice inscribed with symbols have been found on some of the stones following the summer solstice. This monument, which is in the care of English Heritage and has an information board, is difficult to park nearby. Another location (given as OS SY600900) half a kilometre south of the Nine Stones has been recorded as the site of another small circle since destroyed.

A feature described as a cluster of stones has been recorded under some trees in the corner of a field at Little Mayne (SY 723871;LR194.) This was certainly part of the remains of a once larger feature, as another stone lies in a field to the east (SY 724870.) The stones occur mainly on the north side of the road, with a few on a hedge-line on the south side. Minor stone rows also occur nearby. The Little Mayne stones are described by Peter Knight in Ancient Stones of Dorset.

Considerable megalithic activity seems to have been centred around Portesham, with a stone circle surviving on a spur of the coastal ridgeway only 1 km NW of the village. This circle (SY 596864;LR194) also lies just 2.5 km south east of the Kingston Russell circle, while immediately to the north is the area known as the Valley of Stones. The valley is recorded on the Dorset Monuments Record as a possible prehistoric site with a circle of sarsens, of which one sarsen found a few feet north of the circle had been used to grind axes. However, Jeremy Harte of Dorset Archaeology Unit couldn’t find the stone being mentioned in any literature, so with a colleague he checked it out. While certainly unusual it cannot be stated with certainty if the stone is genuinely prehistoric-placed or not. But it is not thought the Valley of Stones has ever been systematically excavated.

Though actually the exposed cairn of a round barrow, the Hellstone, 1 km north of Portesham, broadly resembles a stone circle (ST 606867;LR194.) On Moynes Down near Upton (SY745836;LR194) there is a cairn of stones less than a metre in height set in a circle about 6 feet across. Another circle is said by Charles Warne in Ancient Dorset (1872) to have stood: “..within living memory between East Lulworth and Povington, but not a vestige remains of it remains.” The story goes that the stones were removed by a farmer to build a stream-bridge and two gateposts!