One crisp sunny afternoon late in the autumn a wrong turn found us at the front gates of the Parish Church at Affpuddle, struck by the large churchyard and the regiment of yews. In the spirit of “well, we’re here now” we decided to stay awhile.

The parish is large, at 4,600 acres sparsely populated by 402 people 27% of whom are pensioners, not surprisingly; elsewhere it has been described as a sleepy village. East north east of Dorchester the county town is about seven miles away from this parish the southern boundary of which is the River Frome. Much of the area is heathland, produced by the underlying Reading Beds; it rises to a ridge where there are a number of swallow-holes. One made famous by Thomas Hardy in his novel ‘The Return of the Native,’ where he places Mrs. Wildeve at the lonely and desolate Culpepper’s Dish; said to be named after Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) a figure in the field of herbal medicine. On the north the land, on chalk, slopes to the River Piddle and then rises to another ridge, this is the northern boundary.

Affrith gave land from here in 987 AD to the Abbey of Cerne and it is reasonable to conclude the parish was named after Affrith and the River Piddle. At the Dissolution in 1539 the manor and advowson (the right in English law of presenting a nominee to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice) was given to Sir Oliver Lawrence of Creech Grange, near Steeple, Purbeck. Sir Oliver was the brother-in-law of the Lord Chancellor to King Henry VIII.

The church guide tells us “in 1685 John Lawrence sold the property to William Frampton of Moreton and in 1755 Edward Lawrence sold the mansion and farm to James Frampton. In 1914 Harry Frampton sold the property to Sir Ernest Debenham.” The rich London draper bought farms and cottages in the area with the idea of developing a model estate: in 1952, the estate was sold off in small lots.

The church dedicated to St. Laurence is well set back from the road in its large churchyard from where you have a view to the west of the water meadows. Stroll on to the rear of the church and you will be surprised and delighted to find the River Piddle providing a natural northern boundary to the churchyard and the garden of peace to the east of the church. The Domesday Book talks of a mill at Affpuddle and there is a small-disused mill here, the mill race is a feature of the garden of peace; a seat of Portland and Purbeck stone in memory of local historian Joan Brocklebank is a recent addition to the garden.

The church walls are of rubble and squared Portland stone, in places with alternating bands of flint and carstone, and limestone ashlar and flint in chequered-pattern, with local Ham Hill stone dressings. The roofs are mid 19th century and mainly tiled with some stone slates.

The east window, the smaller chancel pointed window and the trefoil arch of the south door are dated 1230 AD. The nave and possibly the chancel were built about 1200AD, the south porch added in the middle of the 14th century, and the north aisle late in the 15th century. The chancel was rebuilt in 1400 when the chancel arch was enlarged and at this time the south wall of the nave was partly rebuilt and two large windows put in place. The chancel arch includes a hagioscope. On the south side of the arch is an entrance to stairs leading to the rood loft. On the south wall there is a holy water stoup, and in the south chancel wall a piscina with lancet shaped head. In 1840, according to the diary of James Frampton II, the east and south walls of the chancel were taken down and rebuilt. The west tower added towards the end of the 15th century is a good early example of the Perpendicular style.

Before we encourage you to enter the church, we must make you aware of the step down immediately behind the porch door, unprepared for this we fell in landing awkwardly on the hard surface bruising more than our dignity. So do watch your step.

Once inside you will find two Norman fonts both of Purbeck marble but it is the one with the square bowl at the west end of the North Aisle that belongs to this church; the other is in storage from the redundant church at Turners Puddle.

1883 saw the installation of new seating but the carved ends from the original pews have been retained; dated 1547 they are a feature of the church and refer to Lylynton. Thomas Lylynton, a monk at Cerne Abbey, came to Affpuddle as vicar in 1534. The pulpit is from about the same date and is carved with figures, below which are medallions with the symbols of the four evangelists and the fifth, of a pelican.

The church guide tells us “The screen dividing chapel from nave was one of Sir Ernest Debenham’s many gifts to the church. It is partly made from the screen, which used to be at the west end, and this in turn was constructed from the chancel screen.” Another of his gifts is the altar frontal of 15th century Spanish embroidery. The reredos, the figures of St. Laurence and St. Cecilia on the east chancel wall, the Virgin and Child in the chapel, and the crucifix in the war memorial shrine in the garden of peace are all gifts to the church from Sir Ernest.

We consulted three sources for information about the bells and in one respect or another, they all disagreed except in that there are four bells dated 1598, 1655, 1685 and 1722.

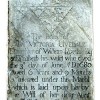

The Lawrence family coat-of-arms found with the monument to Edward Lawrence on the north wall of the chancel is supposed to be the same as that on the signet ring belonging to George Washington, the first President of the United States; the Lawrence family is connected to the Washington’s through an earlier marriage. In claiming that George Washington’s mother was a Miss Lawrence, the church guide may be taking a step too far: George Washington was the son of Augustine Washington and Mary Johnson Ball.

Over the past millennium the church here at Affpuddle has been cared for and improved by Cerne Abbey, the Lawrence, Frampton and Debenham families and no doubt the parishioners, all of whom can be justly proud of the part they have played in preserving and delivering this house of worship to us in the 21st century.